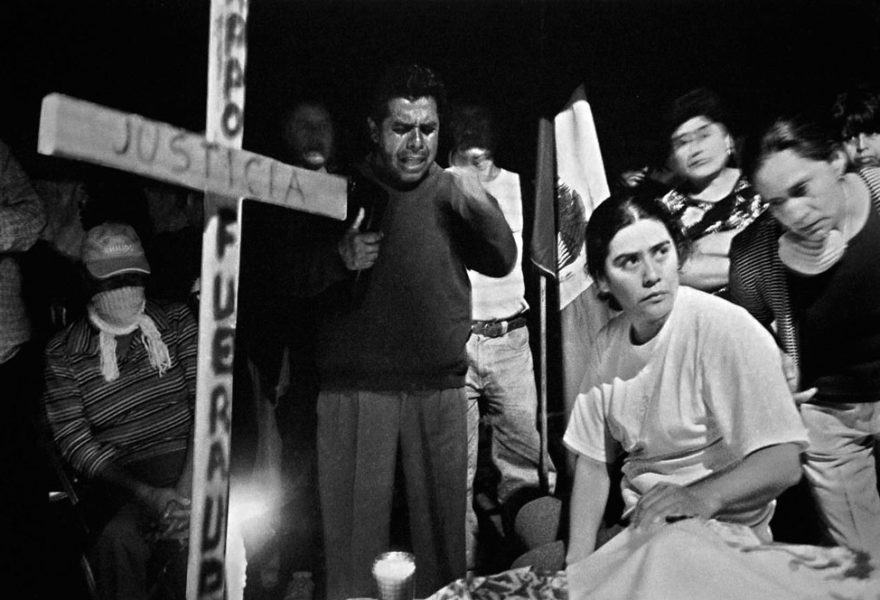

Oaxaca. Teachers movement, 2006

Fights for the power

“Oaxaca is a state full of social problems. Tourism centre in Southern Mexico, its areas of prosperity are surrounded by shantytowns that live mostly, by money transfers sent by migrants by migrant workers. Mainly indigenous and rural, it is one of the two poorest states in the country. Land struggles, confrontations with plantations owners and coyotes, municipalities’ disputes, ethnic claims, actions for better prices for farm products, and resistance to the local government authoritarianism as a part of the daily routine. This economic delay is paired to an archaic, vertical, and oppressive exercise of power. One of the usual traditions of power exercise in Oaxaca is that each new governor that takes possession starts by repressing its opposition, demonstrating to the officials who leave, the political who stay, and the population that suffers, that he is the boss. So he did upon arrival Ulises Ruiz. His anointing as head of the Oaxacan Executive, December 1, 2004, was baptized with the holy water of punishment to his opponents. His path was the same one walked by his predecessors. However, this time the limits of the patience of the Oaxacan people were exceeded”. (Hernández, 2008, 5-6)

appo actions

“The conflict grows exponentially, quickly generating a generalized state of un-governability, presenting moments of great intensity. Over the months that the conflict spread (schematically May to November 2006), the popular movement that agglutinated the appo held various legal actions and policies designed to destabilize the state government and to achieve the output of the representative. On the political side, stand the multitudinous ‘protests’, seven in total (some historic with more than one million participants); taking over of the seats of state powers, as well as the symbolic takeover of public offices through the so-called ‘mobile brigades’; civic and union strikes; roadblocks and highway tolls takeovers; takeover of the International Airport; the takeover of mass media installations to counter the government attacks through the media; the boycott of the Guelaguetza. Permanent sit-in at the Senate, the local Congress, and the Government Palace, among other strategic offices of the public service; the march walk all the way to Mexico City; of course, barricades, symbol of the movement, which at the end of August would extend to virtually the entire city, with the aim of preventing the movement of paramilitary organizations later identified as ‘death caravans’”. (Ávila, 2015, 227)

Government response

“In return, the local and federal government strategy was directed at all times toward a repressive output, canceling the path of political dialogue and the resolution of the conflict through institutional channels, –such as the demand for disappearance of powers in the state– thus contributing to wear down the movement and the polarization of the population, all within the framework of the electoral situation in 2006, and the alliance between the pan and the pri who negotiated the tenure of Ulises Ruiz in exchange for offering quorum and legitimacy in the Federal Congress to Felipe Calderon on his inauguration on December 1 of that year. According to Víctor Raúl Martínez Vázquez (2007: 39), the pri blackmail –‘If Ulises falls, Calderon may also fall’– was the formula that in this situation finally favored the tenure of the Oaxacan representative”. (Ávila, 2015, 227)