Located in the northwestern corner of Mexico, the Tijuana Cultural Center (CECUT-Centro Cultural Tijuana) has focused its efforts in understanding migration. That is why, the current administration has pushed for a plethora of projects that emphasize the different issues, both national and international, that come with the movement of people across the border and how all of this impacts on their identities and sense of belonging.

Construyendo puentes en época de muros. Arte Chicano / Mexicano de Los Ángeles a México exhibition allows us to Delve into what it means to migrate for those who live through it: the search for an identity, the economic relationships that they establish, the new communities that appear and the implicit narratives of a population with different origins. Being in one of the most crossed borders into the US makes for the CECUT to be honored as its final host, after having traveled thorough Mexico.

Although the exhibition was originally conceived for people to physically attend it, this new digital experience gives us the advantage of reaching audiences that hadn’t originally planned to attend; this in turn expands the capabilities of the exhibition to be appreciated.

The exhibition, originally programmed to be presented and enjoyed on a physical manner, is strengthen on this digital plane because it can reach new audiences, it can dialogue with different publics on a wider space and, therefore, it can have different readings.

CECUT celebrates all kinds of creative forms and expressions that contribute to sensitize about migratory issues and the rich cultural diversity that exists in our society.

curatorial text

Artists: Roberto de la Rocha, Gilbert “Magu” Lujan, Frank Romero, Patrick Martinez, Johnny “KMNDZ” Rodriguez, Jose Ramirez, Enrique Castrejon, Judy Baca, Donna Dietch, Carlos Almaraz, Gil Garcetti, Ana Serrano, Shizu Saldamando, Gary Garay, Ramiro Gomez, Einar and Jamex de la Torre, Viviana “Viva” Paredes, Man One, Eloy Torrez, Patssi Valdez, Roberto Gil de Montes, Gronk, Yolanda González, Judithe Hernández, Linda Vallejo, Gabriela Ruiz, John Valadez, and Leticia Maldonado.

Over 50 years of existence, the ever-evolving Chicano art has shaped itself into one of the main movements of the American creative canon. Established among four cultures ―the Pre-Columbian, the invasive Hispanic, Mexico itself and the United States of America― Chicano art draws on all four and evolves out of both its roots and the decades of oppression its practitioners and their families have sustained.

Since the violent benchmark the 1970 Moratorium street clash in East Los Angeles, California, Latinos have made progress economically, socially and politically. However, Chicanos and Latinos continue to be a marginalized group ―outsiders― in their own home in the United States and even in Mexico. This has continued to be the case even as the Latino population proportion in major US cities (such as Los Angeles, New York and Chicago) has grown in size as well as in political power.

Born in the middle 1960s ―along with Vietnam War protesters and the Black Power Civil Rights movement― the Chicano statement challenged racial categorization and derisive stereotypes widespread in the Anglo population as well as the dropout-riddled public education establishment that proclaimed Latinos too inferior to attain a middle-class standard of living.

These issues became the subjects of early Chicano artists. The expressionistic, outspoken realism of their works appealed to an art public that had become jaded by successive establishment trends in non-representative painting.

Through highly developed skills and originality, these artists of dual Mexican American heritage, opened the windows into Latino culture, not just by marking the conflicts with Anglo society, but also by flaunting, celebrating and elevating aspects of Latino culture and tradition that the Anglo world could no longer ignore.

The advancements and hardships of the past five decades have helped to shape Chicano and Latino art’s evolution. These artists have expanded their creative expression, demonstrating an agility to develop and refine their own mythologies, methodologies and philosophies. They have introduced a remarkable, original school of art into the history of art itself.

This exhibit brings a multigenerational selection of works by Chicano and Latino artists from Southern California, all of whom are of Mexican heritage. The exhibit examines how these artists explore their cultural hybridity through five significant themes: Rebel Diamonds from the Sun, Imagining Paradise, Outsiders in their Own Home, Mapping Identity and Cruising the Hyphenate. Simultaneously, in widening the lens of how Chicano and Latino art is viewed beyond its strict geographical home, the exhibit illustrates these artists’ inexorable ties to Mexico and how they transcend singular identity and borders.

By no means does this exhibit intend to serve as a definitive survey of Chicano art; nor does it present itself as the sole arbiter ―or final word― in defining what is or isn’t Chicano art. On the contrary, this exhibit continues the exploration of Los Angeles art in dialogue with Mexico, signifying a historic moment by the presenting Chicano art as original school of American art.

node 01

Chicano art began in the 1960s as the collective grito ―scream― of this aroused population to confront the majority Anglo culture. Latino soldiers were dying in disproportionate numbers in Vietnam. Latino fieldworkers were struggling with terrible work conditions and ridiculously low wages in the vegetable fields of California’s Central Valley. Meanwhile, in the barrios, law enforcement had stepped up arrests of ice-cream street vendors and young Chicano motorists accused of illegally “cruising” ―re-imagined fact in Frank Romero’s The Closing of Whittier Boulevard―. The movement artist avatars were aroused by the systemic injustice pointed directly at the barrio’s inhabitants. Their concerns were voiced by this engaged and growing cadre of supremely talented young individuals who put their artwork first as murals on the walls of their communities, then in publications and museums, and ultimately before a startled American public. They were practicing what Italian philosopher Umberto Eco called “semiotic guerrilla warfare”.

Decade after decade, these artists continue to rise up and empower others to effect change. They are determined to be recognized and accepted. They are Chicano and Latino artist who have evolved mightily since the 1970s. As their theory, skills, and ideals have developed, critics have both berated and congratulated them for moving on from message making to the ideals of fine art.

These are the Rebel Diamonds from the Sun, forged by the intense pressures of injustice and marginalization only to emerge bright hot and nigh unbreakable, as their creative expressions and processes expand, deepen and mature.

node 01

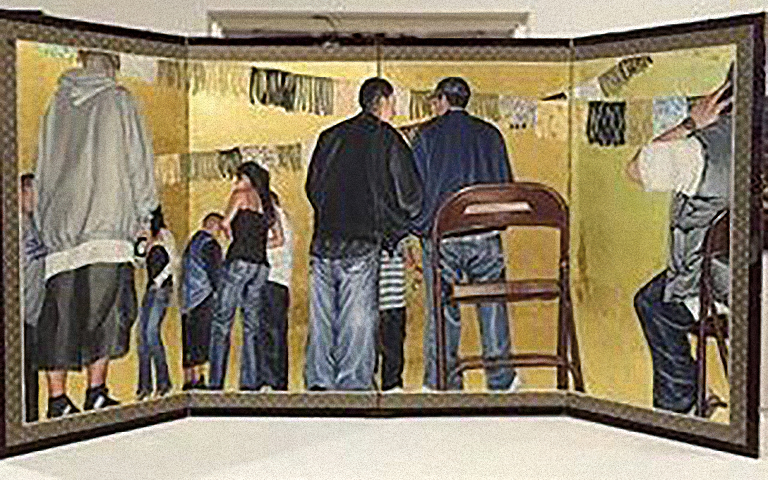

Los Four (Roberto «Beto» de la Rocha, Gilbert «Magu» Luján y Frank Romero)

Los Four 20th Anniversary Collective Mural, 1994

Acrylic on wood panels / 72 x 192 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 01

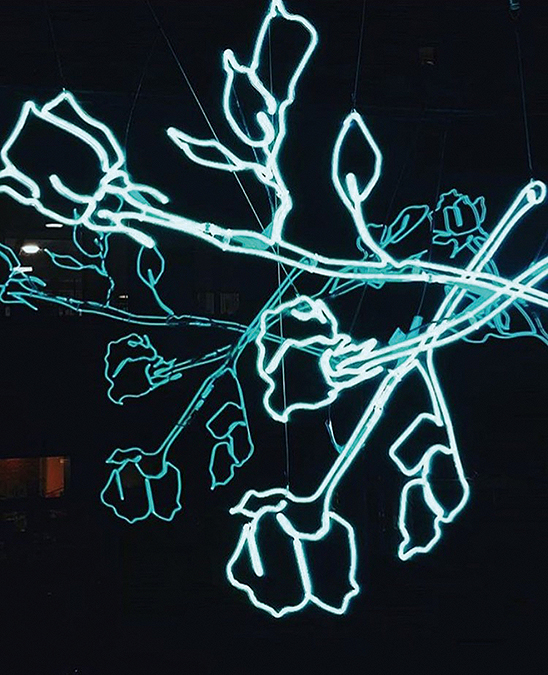

Patrick Martínez

America is for Dreamers, 2016-17

Neon installation / Various sizes

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 01

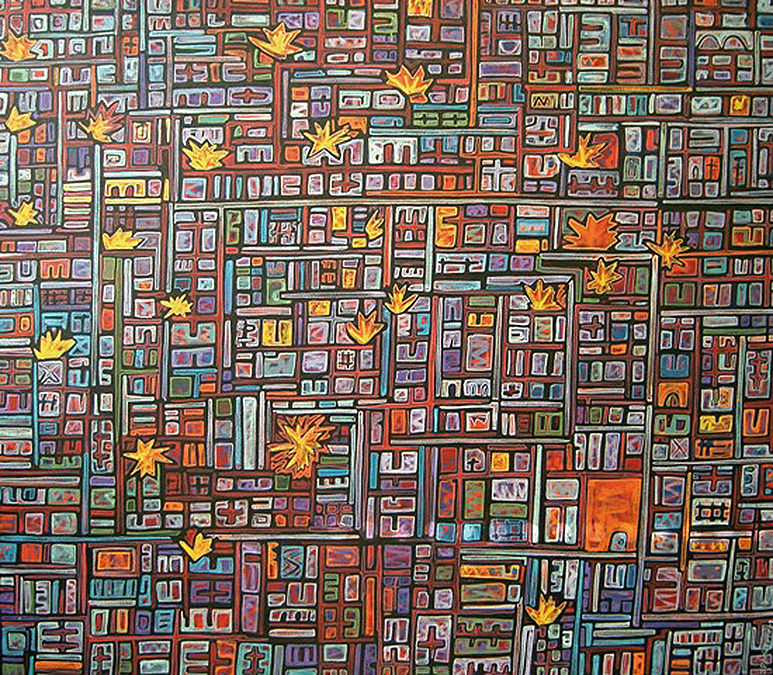

Jose Ramirez

Middle East L.A., 2009

Mixed media on canvas / 67.5 x 77.25 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 01

Judy Baca and Donna Deitch

Judy Baca as La Pachuca, 1976

Archival digital print on photographic paper / 24 x 24 in.

Courtesy of Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC)

node 01

Judy Baca and Donna Deitch

Judy Baca as La Pachuca (I, II, III), 1976 (reproduced 2018).

Archival digital print on photographic paper / 38.5 x 38.5 in.

Courtesy of Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC)

node 01

Judy Baca and Donna Deitch

Judy Baca as La Pachuca (I, II, III), 1976 (reproduced 2018).

Archival digital print on photographic paper / 38.5 x 38.5 in.

Courtesy of Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC)

node 01

Judy Baca and Donna Deitch

Judy Baca as La Pachuca (I, II, III), 1976 (reproduced 2018).

Archival digital print on photographic paper / 38.5 x 38.5 in.

Courtesy of Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC)

node 01

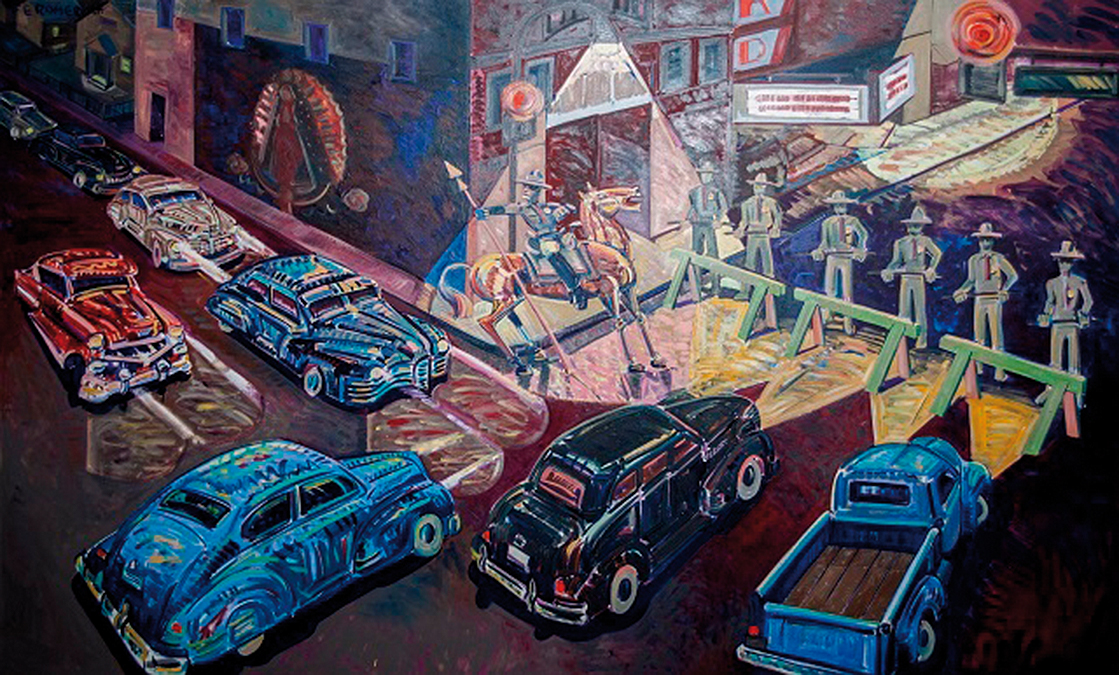

Frank Romero

The Closing of Whittier Boulevard, 1984

Oil on canvas / 66.25 x 108 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 01

Jose Ramirez

Lucha, 2016

Charcoal on paper / 37 x 38 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 02

Los Angeles is often called the “City of Dreams”. It is a place that includes its own dream factory (Hollywood), consumer mecca (Rodeo Drive), and make-believe world (Disneyland), not to mention a subtropical Mediterranean climate, beaches, wetlands and mountains. Such a myth requires ignoring the indigenous and Mexican population already there. Hollywood helps to sustain that myth, since one rarely sees the city’s Latino majority depicted in studio feature films or network television series set in Los Angeles. But for the Mexican-descent population in Los Angeles, the “City of Dreams” ―that modern sense of the region as a paradise— came at their expense as freeways cut through their communities, and as a social institutions either neglected or discriminated against this population, isolating Chicanos from a city their ancestors had founded.

This history is often narrated in the social and political terms of the mid-century civil rights movements in the United States. But the arts were a critical element of this effort, placing the act of seeing on equal footing with rights-based demands. In claiming a space and an intention for their work, these artists offered both a critique of the society and an alternative social vision, leaving the aesthetic as an undefined area to be answered by the work itself.

In Imagining Paradise, these artists produce works that are at once insistent and ambiguous, calling the “City of Dreams” to account, while still dreaming nonetheless.

node 02

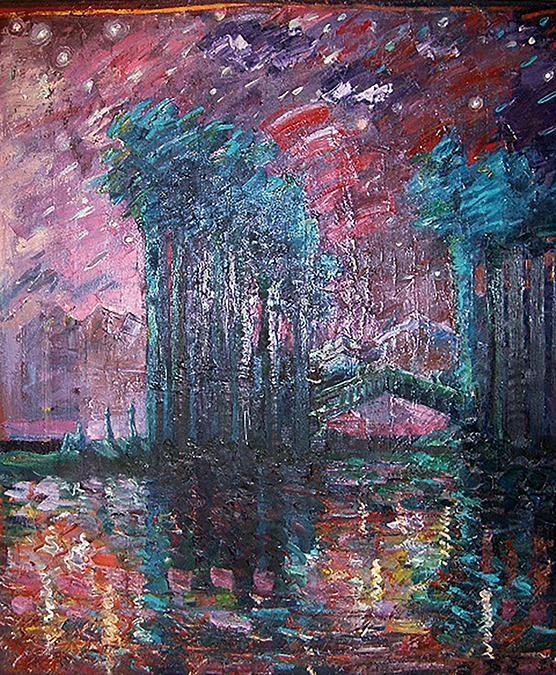

Carlos Almaraz

The Bridge in Deep Magenta, 1984

Oil on canvas / 60.5 x 50.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 02

Carlos Almaraz

Yellow Morning, 2015

Oil on canvas / 72 x 108 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 02

Gil Garcetti

Los Angeles Skyline (from Dodger Stadium), 2011

Chromogenic print / 11 x 16 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 02

Gil Garcetti

Panorámica de Los Ángeles (from City Hall), 2017

Chromogenic print / 11 x 16 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 02

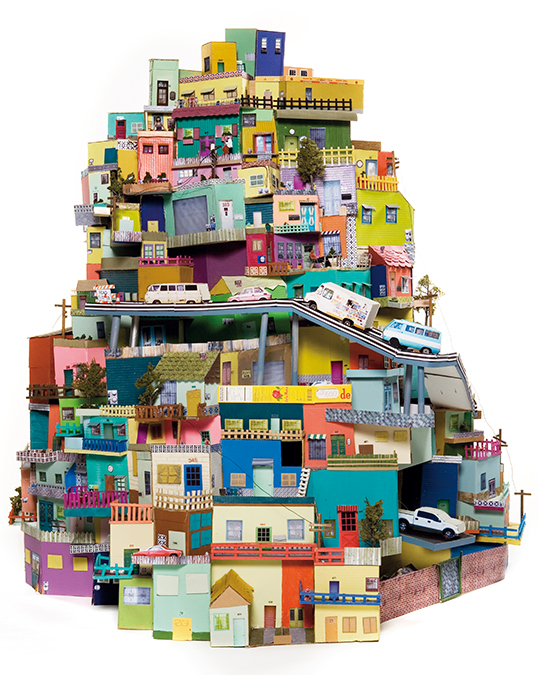

Ana Serrano

Cartonlandia, 2008

Cardboard, paper, acrylic, and glue / 60 x 48 x 54 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 02

Shizu Saldamando

Highland Park Luau, 2006

Oil and collage on found screen / 32 x 64 in.

Courtesy of Ricardo Padilla Reyes

node 03

Histories of immigration, shifting demographics, and the impact of transnational trade policies like NAFTA have been points of departure for artists, curators and critics alike. Whereas exile and diaspora are issues that are inextricably bound to certain Latin American and United States based Latino artists, especially those directly impacted by displacement, the Chicana/o artist has a complex and fraught relationship to homeland because a binational —or even transnational— identity that is betwixt and between or “ni de aquí ni de allá”.

In the visual arts, Chicano art absorbs and redefines art movements like pop, neo-expressionism, and the like, but on an existencial level, it broaches the uncertainties of identity and belonging in relation to this betweenness. Many of the works in this section, save Viva Paredes’ sculpture A Blessing for a Wetback (2010), are figurative representations. Bodies at work have been an inextricable part of Chicano art with representations of migrant farmworkers laboring under Central Californian skies depicted frequently in murals, paintings and political graphics.

Figurative representations have often been the site in Chicano art for a reimagining and affirmation of identity, but references to the laboring body in this section are more likely under threat or surveillance, criminalization, and/or disappearance. The policing or scripting of activity in public or private spaces is a major concern to those perceived as extralegal, “outsiders” or “aliens”.

Location and dislocation define the spatial and temporal conditions of Chicano identity. Ironically, the avant-garde has historically championed marginal or so-called outsider artistic practices, such as that by self-taught or “folk” artists. For Chicano artists, their “outsider” status is not only tied to being suspicious of the mainstream artistic networks of power, but a broader questioning of the fixity of identity and national belonging.

node 03

Gary Garay

Paleta Cart, 2004

Customized paleta cart with lacquer and enamel / 36 x 46 x 33 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 03

Ramiro Gomez

Domestic Scene, Beverly Hills, 2013

Acrylic on two magazine leaves / 11.5 x 16 in.

Collection of Alfred Fraijo Jr. and Arturo Becerra-Fraijo

node 03

Ramiro Gomez

Ismael Waiting for his Check, 2013

Acrylic on magazine leaf / 11.5 x 8 in.

Collection of Alfred Fraijo Jr. and Arturo Becerra-Fraijo

node 03

Jamex and Einar de la Torre

Border Park of Earthly Delights, 2014

Cast resin, found objects, lenticular, and LED light box in aluminum frame / 48 x 63 x 5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 03

Viviana «Viva» Paredes

Bendición Para Un Mojado (A Blessing for a Wetback), 2010

Blown glass, medicinal herbs, reclaimed wood, and steel / 84 x 96 x 20 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 03

Ramiro Gomez

Lupita, 2017

Painted bronze / 60.25 x 45 x 11 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 03

Man One

ALIENATION, 2014

Acrylic and aerosol on panel / 48 x 96 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 03

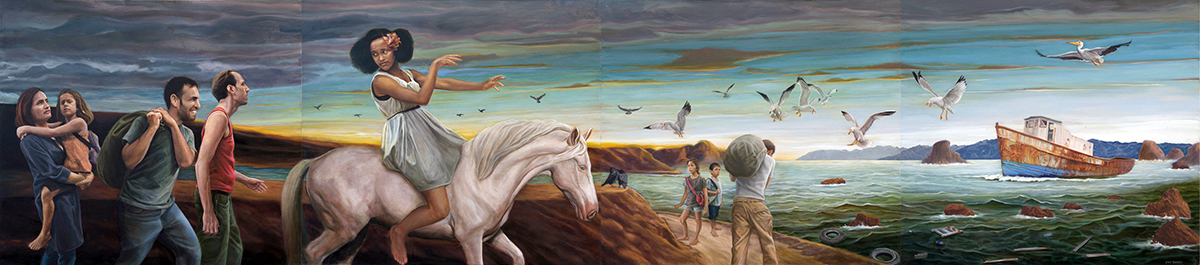

Eloy Torrez

Migration, 2000-2005

Oil on canvas / 33.25 x 150.25 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 03

Ramiro Gomez

A Lunchtime Conversation, 2015

Acrylic on cardboard / 70 x 36 x 36 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 03

Patssi Valdez

Pan Mexicano (The Merging of Two Cultures), 2017

Acrylic on canvas / 36 x 48 in.

Collection of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 03

Roberto «Beto» de la Rocha

Soy Mestizo (Color), 1974

Pastel, watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper / 21 x 31.5 in.

The de la Rocha Family Collection

node 03

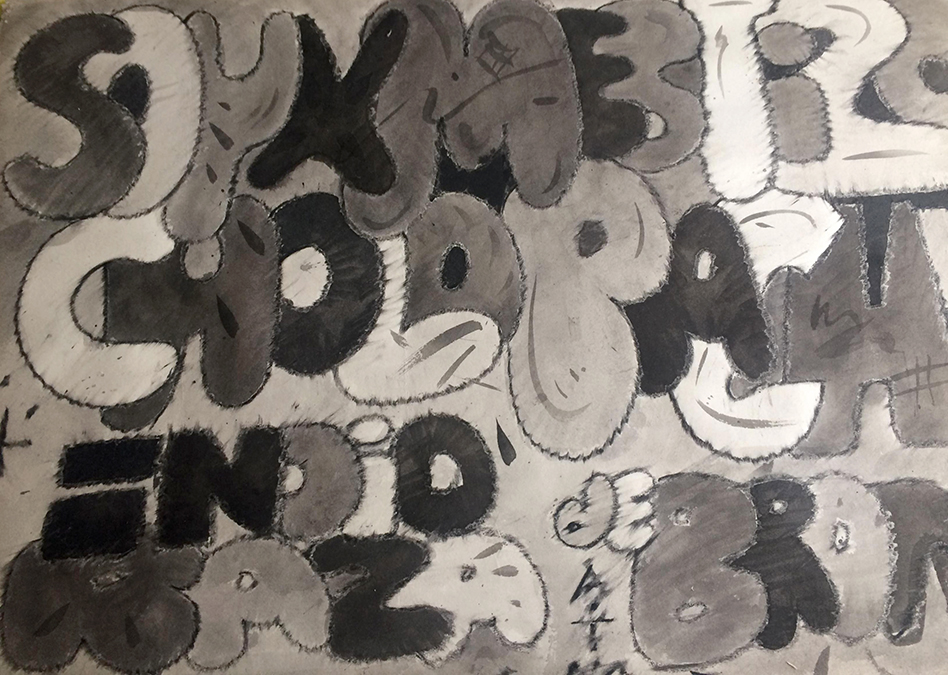

Roberto «Beto» de la Rocha

Soy Mestizo (Black and White), 1974

Charcoal and ink on paper / 21 x 31.5 in.

The de la Rocha Family Collection

node 03

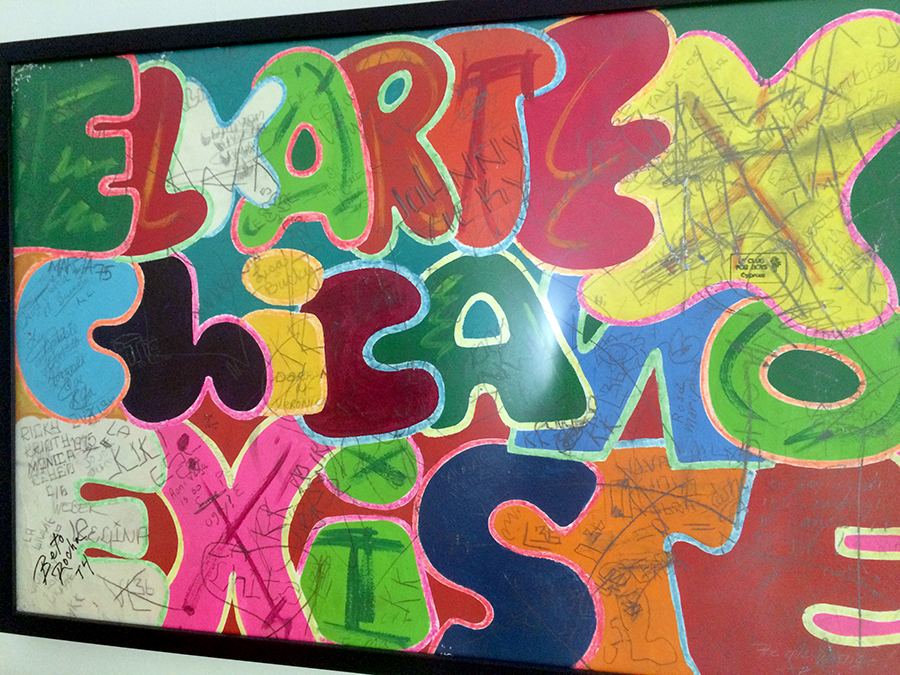

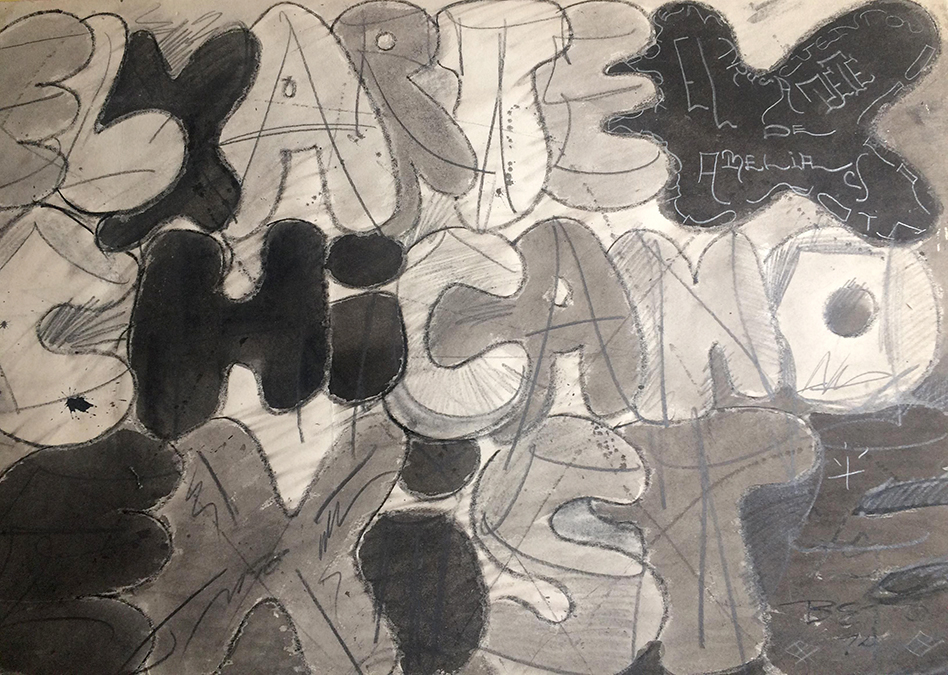

Roberto «Beto» de la Rocha

El Arte Chicano (Color), 1974

Pastel, watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper / 21 x 31.5 in.

The de la Rocha Family Collection

node 03

Roberto «Beto» de la Rocha

El Arte Chicano (Black and White), 1974

Charcoal and ink on paper / 21 x 31.5 in.

The de la Rocha Family Collection

node 03

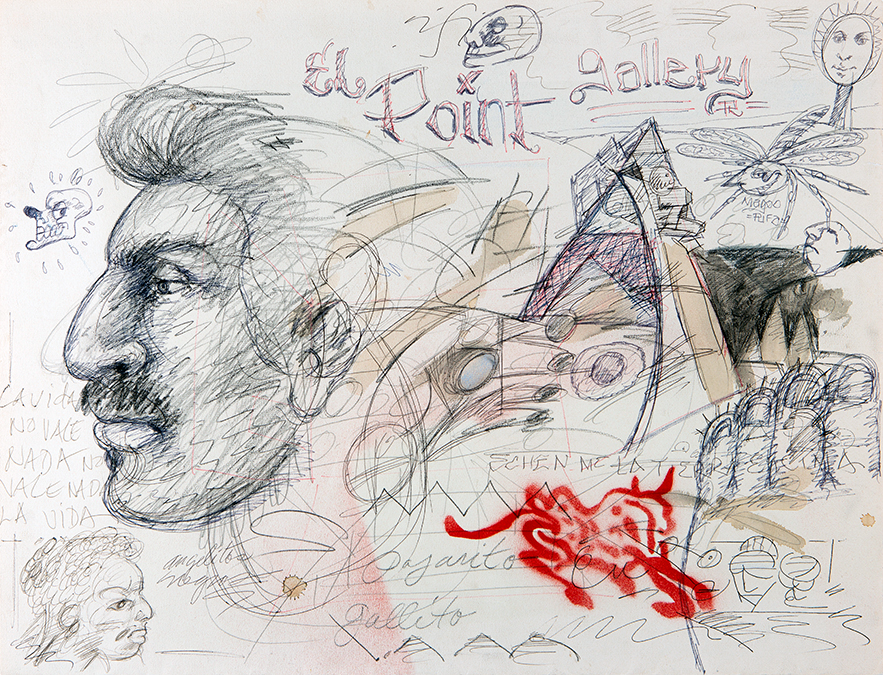

Los Four (Carlos Almaraz, Roberto «Beto» de la Rocha, Gilber «Magu» Luján and Frank Romero)

El Point Gallery, c. 1970s

Ink, pencil, stencil, and color pencil on paper / 23 x 29 in.

The de la Rocha Family Collection

node 04

Identity, as a core expression of one’s subject position, is a recurrent topic in Chicano art. Set against the racialized systems of the US and within the context of the complex matrix of the borderlands —a concept that moves beyond geographies to inhabit the self— the space of identity is not fixed or stagnate, but is rather negotiated and constantly evolving. Identity emerged as a critical subject in US Latino art in the twentieth century, often reflecting the in-betweenness of nationalisms and bifurcated cultural imaginaries of the immigrant experience, and in relationship to histories of colonization.

The Chicano Art movement concretized the importance for speaking about identity as a means of empowerment and self-awareness. The era of Identity Politics in the 1980s and early 1990s that followed reflected deep inquiry into the subject, which in turn was trailed by a rejection of identity-based art beginning in the mid-to-late 1990s, played out against the backdrop of the rise of globalism at the turn of the 21st century. In the current millennial period, intersections and the cross-pollinating of images, ideas and concepts worldwide situate issues of identity in Chicano art within globalized discourse. In this expanded playing field, identity finds renewed footing in our multiplatform image-based era.

Chicano art has developed not only as an expression of political and collective identity, but is also reflective of an incredibly diverse and nuanced landscape of artistic practices, ranging from engagement with any and all major art movements, interrogating areas of personal artistic exploration, addressing questions of gender, race, class and more. The notion of mapping identity is one that allows us to survey and contemplate responses to broad cultural questions, including the politics of positionality and place, and gestures that denote both inner and outer worlds of the self.

node 04

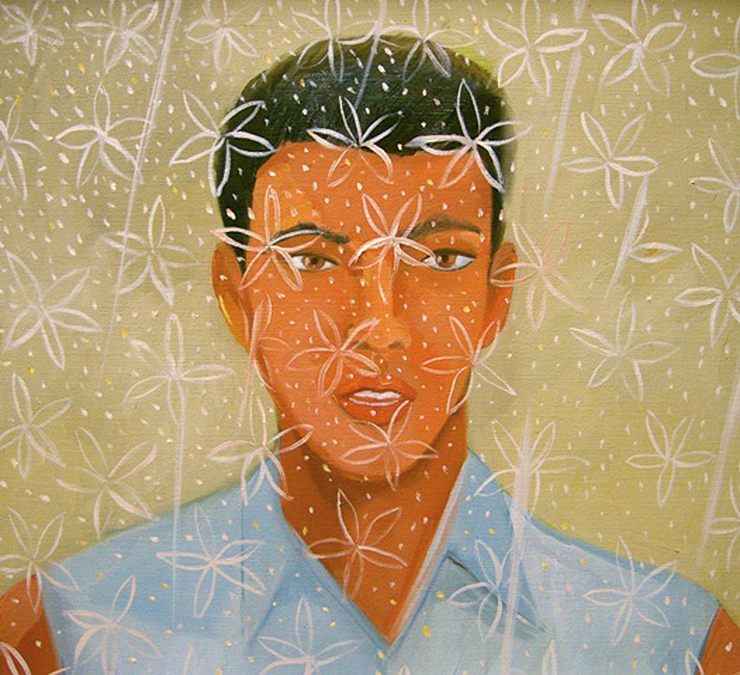

Roberto Gil de Montes

Untitled, 2007

Oil on linen / 24 x 24 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

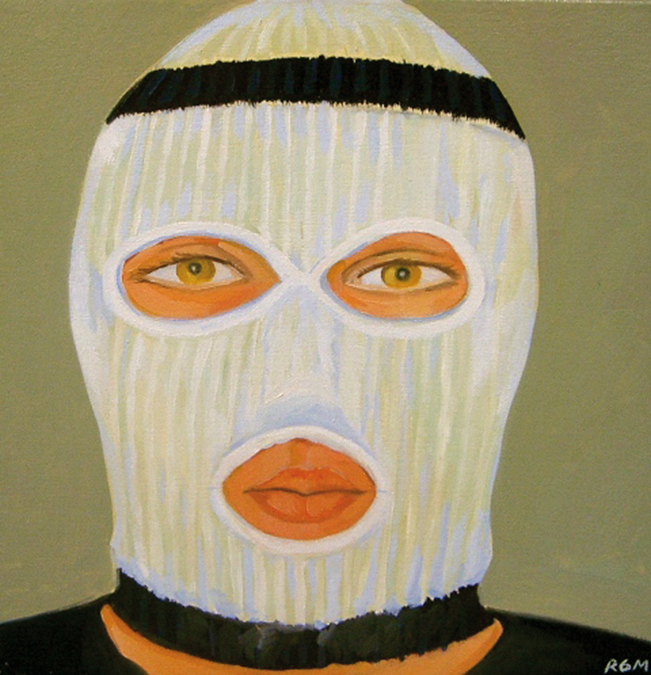

Roberto Gil de Montes

Ski Mask, 2005

Oil on canvas on board/ 13.75 x 13.75 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

Gronk

Griselda, 2009

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas / 62 x 62 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

Yolanda Gonzalez

Reaching for Insanity: Metamorphosis Series, 1990

Acrylic on canvas / 72 x 72 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

Yolanda Gonzalez

Blue Conga, 1990

Acrylic on canvas / 48 x 48 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

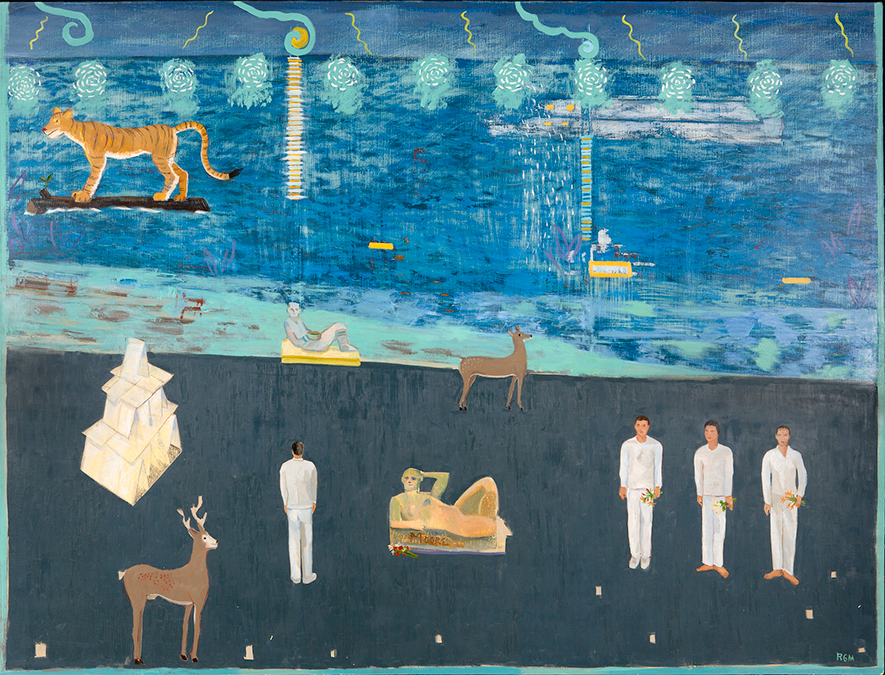

Roberto Gil de Montes

Henry Moore, 2014

Oil on linen / 75 x 98.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

Judithe Hernandez

L’EPPE DE SAINT JEANNE (The Sword of Saint Joan), 2013

Pastel and mixed media on canvas / 40x 60 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

Judithe Hernández

THE PURIFICATION (La Purificación), 2013

Pastel and mixed media on archival wood panel / 30 x 40 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

Linda Vallejo

The Brown Dot Project: 4.5% of US Latinos are 69+ Years Old, 2017

Repurposed photograph, pigment print, non-photo blue pencil, archival marker / 11 x 8.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

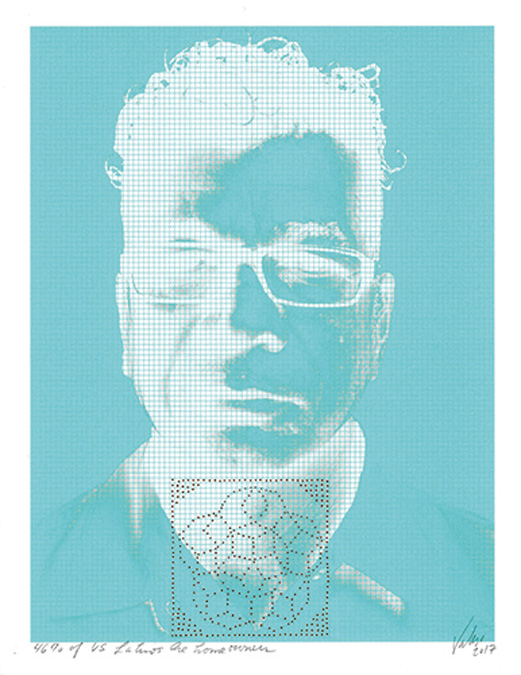

Linda Vallejo

The Brown Dot Project: 46% of US Latinos are Homeowners, 2017

Repurposed photograph, pigment print, non-photo blue pencil, archival marker / 11 x 8.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

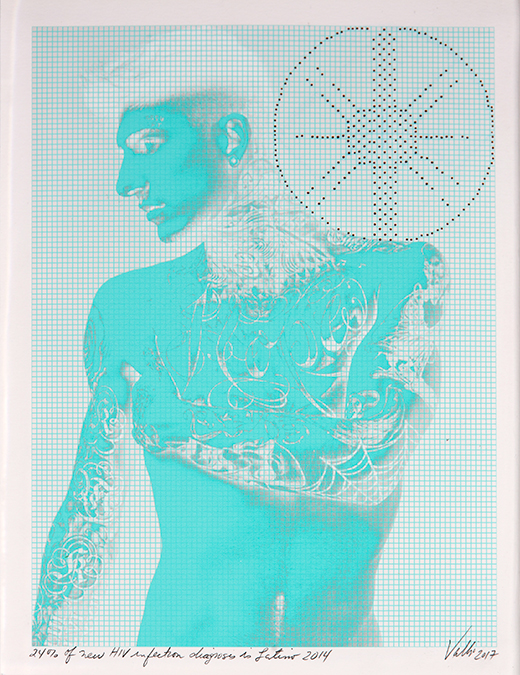

Linda Vallejo

The Brown Dot Project: 24% of New HIV Infection diagnosis is Latino, 2017

Repurposed photograph, pigment print, non-photo blue pencil, archival marker / 11 x 8.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

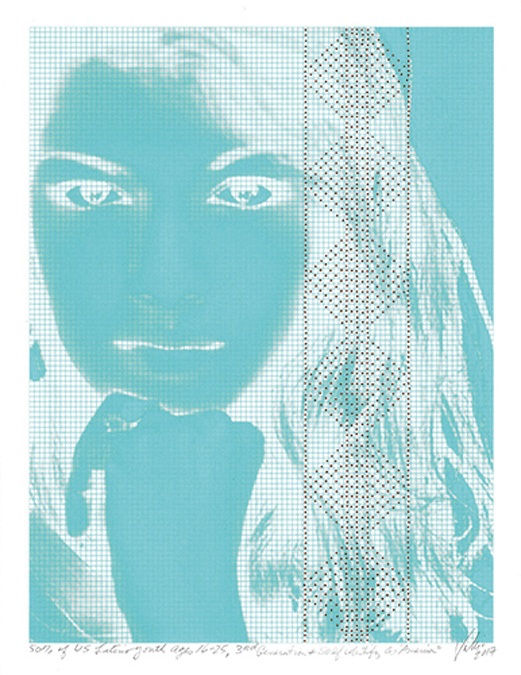

Linda Vallejo

The Brown Dot Project: 50% of US Latinos Youth Ages 16-25, 3rd Generation, Self-Identify as American, 2017

Repurposed photograph, pigment print, non-photo blue pencil, archival marker / 11 x 8.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

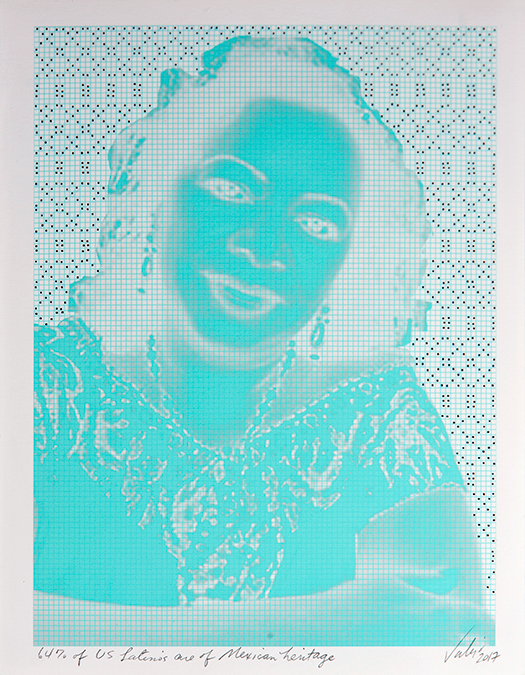

Linda Vallejo

The Brown Dot Project: 64% of US Latinos are of Mexican Heritage, 2017

Repurposed photograph, pigment print, non-photo blue pencil, archival marker / 11 x 8.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

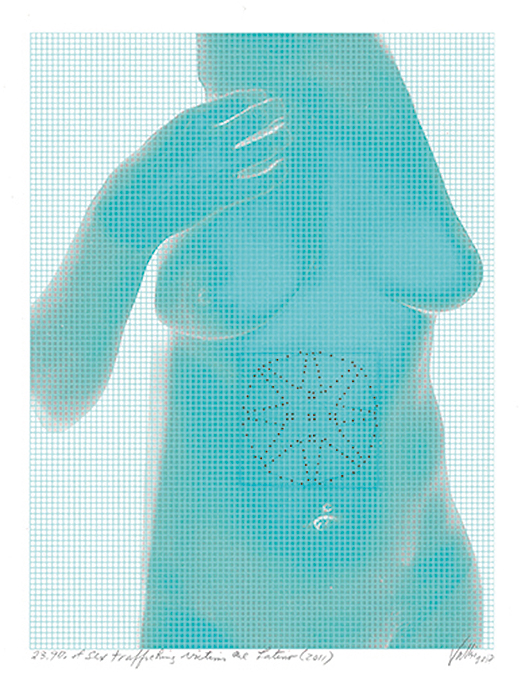

Linda Vallejo

The Brown Dot Project: 23.9% of Sex Trafficking Victims are Latino, 2017

Repurposed photograph, pigment print, non-photo blue pencil, archival marker / 11 x 8.5 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 04

Enrique Castrejon

Anatomy of a Kiss, 2016

Collage, glue, acid-free adhesive tape, and pigment ink on ripped paper / 8 x 8 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

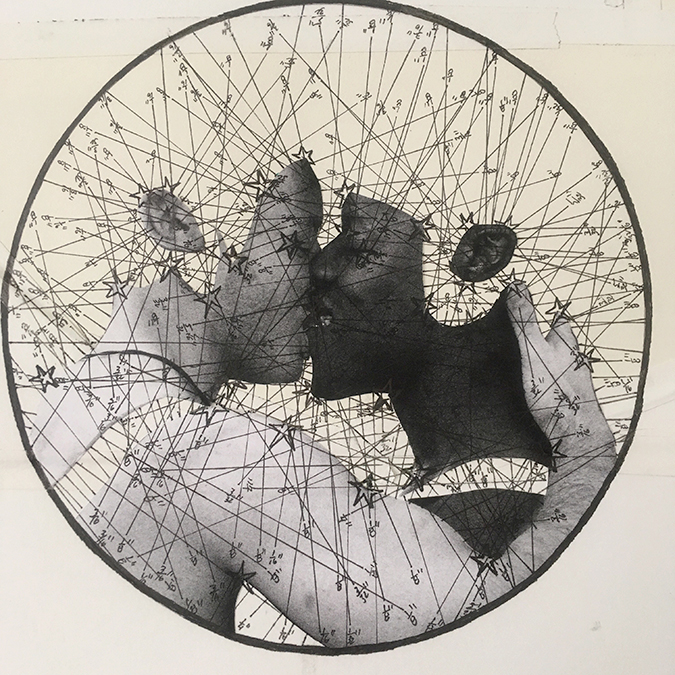

Enrique Castrejon

The Stars We Are, 2016

Collage, glue, acid-free adhesive tape, and pigment ink on ripped paper / 8 x 8 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

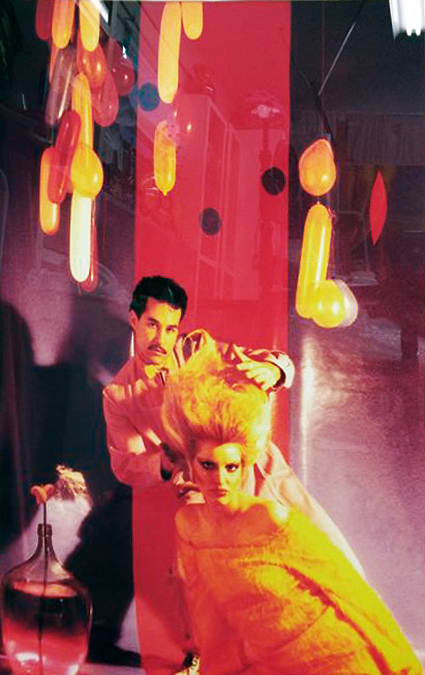

Patssi Valdez

Portrait of Sylvia Delgado, c. 1980

Mixed media photo collage / 50 x 43 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

Patssi Valdez

Phyra, c. 1980

Mixed media photo collage / 24.6 x 30.7 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

Patssi Valdez

Portrait of Anthony Villareal and Dede Diaz, c. 1980

Digital print / 33 x 24 in.

Courtesy of the artist

node 04

Gabriela Ruiz

A Cinderella Story for Everyday Objects, 2018

Site-specific DIY installation integrated with locally-sourced objects from Mexico City and re-imagined by the artist.

Courtesy of the artist

node 05

While appearing to be a simple, innocuous punctuation mark used for joining words or demarcating the syllables of a single word, the hyphen is a much more powerful symbol capable of uniting just as easily as it can divide. As a bridge, the hyphen can bring together two cultural identities, such as “Mexican-American” or “African-American”, allowing both cultures to co-exist while maintaining their distinct characteristics. However, in keeping with its nature, the hyphen isolates and differentiates in order to highlight the specific qualities of the words it is actually separating.

“Mexican-Americans”, “Latino-Americanos”, “French-Canadians”, are hyphenated groups who are active in more than one sphere. Cars are metaphoric hyphens. Although they isolate us from the rest of the world, they can be consciously, actively exercised to traverse new experiences and places.

Centered around the freeway capital of the world, Los Angeles Chicano culture naturally drinks deeply of the ultra-mobile-four-wheeled civilization of the 20th century. It was this popular fascination that created the “Low Rider”, one of Chicanismo’s major gifts to modern technology. And naturally, Chicano art reflects the Eastside Aztlan’s almost spiritual obsession with the car in general —the vintage Chevrolet in particular— as a symbol of freedom, mobility, sanctuary and transcendence.

The mobile culture of the 20th century brought a sense of freedom, allowing individuals to traverse far and wide, moving beyong their neighborhoods and cities. The vehicles which were used provided escape, exploration, expansion, and growth both literally and metaphorically. In a sense, the cars themselves act as vehicles of transformation. And, similarly, neon serves as a metaphor for transformation and transcendence, as it also straddles two worlds —historic and modern— like those of Mexican and American heritages.

By actualizing their vision during the creative process or by reaffirming their artistic and cultural identity, the artists in this exhibit have allowed themselves to transcend social labels and move beyond others’ perceptions of who they are based on strict geographical boundaries.

node 05

John Valadez

Drive-in, 2014

Acrylic on canvas / 98 x 122 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 05

Johnny «KMNDZ» Rodriguez

Atascado, 2015

Acrylic and aerosol on panel / 48 x 60 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar

node 05

Frank Romero

Urban Landscape, 1989

Aluminum and copper / 36 x 60 x 3.5 in.

Courtesy of Deloitte

node 05

Leticia Maldonado

Strewn, 2018

Installation of ten 8mm glass tubing pumped with argon/mercury (neon) / 5 x 18 x 4 feet

Courtesy of the Fisher Family Collection, Spadaro Collection, and Juan Velasco

node 05

Johnny «KMNDZ» Rodriguez

Palindrome, 2019

Set of 2. Acrylic on wood panels / 96 x 48 in.

AltaMed Art Collection, courtesy of Cástulo de la Rocha and Zoila D. Escobar